Here's two books on Barry Goldwater that I'm dying to read. The first, entitled Pure Goldwater, was co-authored by Barry Goldwater Jr. and John W. Dean (of Watergate fame), but was also relied heavily on Goldwater's private journals. Michael J. New, reviewing the book for National Review Online, wrote:

Here's two books on Barry Goldwater that I'm dying to read. The first, entitled Pure Goldwater, was co-authored by Barry Goldwater Jr. and John W. Dean (of Watergate fame), but was also relied heavily on Goldwater's private journals. Michael J. New, reviewing the book for National Review Online, wrote: "Of all the books on “Mr. Conservative,” Pure Goldwater might provide the most realistic insights into his character and thinking. After the birth of Barry Jr., Goldwater started a private journal, which he maintained off and on throughout his career, to record for the benefit of his children his thoughts on a range of topics — including running his business, his military service during World War II, the natural beauty of Arizona, and his long career as a U.S. Senator. That journal is the basis of Pure Goldwater — so, in effect, it is a book written by the senator himself, capturing his most intimate thoughts for those closest to him."

According to New, the book barely touches upon Goldwater's 1964 campaign for President, his various successful Senatorial campaigns, or his relationship with Ronald Reagan. New wrote that "the book offers invaluable insights into Goldwater’s dealings with Richard Nixon — as a Presidential candidate, as President, and in the aftermath of the Watergate scandal — which together comprise roughly a third of the book."

The book also includes personal letters and speeches of as well as tributes to Goldwater.

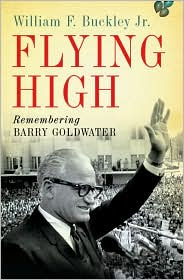

The other book is William F. Buckley's Flying High: Remembering Barry Goldwater. This book is as much about Buckley as it is about Goldwater. Reviewing the book for City Journal, Michael Knox Beran wrote:

"The generosity with which old adversaries treated William F. Buckley, Jr., after his death in February was double-edged. They praised the man and deplored his ideas. “He was a cultivated man,” Hendrik Hertzberg wrote in The New Yorker. “He could not have been happy with the vulgarity of the movement he did so much to spawn.” Hertzberg justified his eulogy by arguing that Buckley had changed: after Ronald Reagan became president, he “began to drift away from the militant conservative movement and its orthodoxies—not as spectacularly as his friend Barry Goldwater, but perceptibly. His political writings became perfunctory; he preferred to write thrillers (and pieces about sailing for The New Yorker).” If Hertzberg were right, Flying High: Remembering Barry Goldwater—the last book Buckley saw through the press—would presumably give some indication of his estrangement from the movement to which he and Goldwater devoted the energies of their prime."

"It doesn’t. Flying High is not a recantation. In it, Buckley describes the “grand time” that he and Goldwater had leading the conservative counterrevolution against the orthodoxies of the Left and against those Republicans—like Nelson Rockefeller and John Lindsay—who accommodated them. This aboriginal right-wing conspiracy succeeded when Goldwater won the Republican presidential nomination in 1964 and campaigned on the principles of his 1960 book, The Conscience of a Conservative. Buckley’s brother-in-law, National Review editor L. Brent Bozell, ghostwrote the book, which lamented America’s betrayal of the idea of limited government and drew attention to some of the consequences of that betrayal: “an immense tax burden, high consumer prices, vexatious controls.” Buckley admits that he and his fellow conspirators made mistakes. They had not yet found a way to sell conservatism to the nation as a whole. Goldwater’s rhetoric was at times too strident; Buckley shows Ronald Reagan, about to launch his own political career, carefully taking note."

" Goldwater is remembered today mainly as Reagan’s unsuccessful forerunner, but Buckley, a master of the éloge, shows that there was much more to the man. In Flying High he evokes not only the politician but also the pilot, the naturalist (“a child of the Grand Canyon”), the eccentric (Goldwater arrived in Palm Beach in 1962 wearing denim jeans, a cowboy hat, and cowboy boots), and the loyal—but always honest—friend. (Asked how Buckley had acquitted himself performing a harpsichord concerto in Phoenix, Goldwater said: “Wonderfully. Absolutely first rate. Of course, this is the first time I ever went to a concert.”) Goldwater’s decency, too, is manifest. Advised to make political hay of LBJ’s disgraced aide Walter Jenkins, who had resigned in a sex scandal, Goldwater shook his head. “Jenkins has a wife and six children,” he said. “Leave him alone.”"

"Flying High is not the work of a disenchanted conservative. It is, however, the work of a man who recoiled from repetition, a restless writer continually working out new literary forms. While he might not have indulged in what J. S. Mill called “experiments of living,” Buckley had no patience with the notion that a conservative must conform to the established aesthetic modes."

"A political movement cannot, of course, inspire in maturity the same excitement it did in its earliest and most revolutionary phases. Bill Buckley, in the sunset of life, had a degree of nostalgia for the “joys and sorrows” of the early days of the conservative revival. But he did not drift away from the movement he founded. Flying High, his last book, is not a work of disillusion. It is the work of a man faithful to his earliest inspirations, and highly original in his literary representation of them."

No comments:

Post a Comment